Culture shock. This is the feeling of anxiety we often get when exposed to a cultural environment that we are unfamiliar with.

There are many factors that contribute to the feeling of culture shock: the way we were raised, the values we believe in, and the culture we have previously been exposed to. As early as when we are a few months old, these factors start to have an effect, and we begin to develop our own sense of “culture” and “diversity.” This sense adjusts over time as we interact with the world and the society around us. The lessons we take away from each of these interactions then play a crucial role in shaping the development of this sense. The greater varying and further differing interactions we have, the more we are able to expand our understanding of the broad definitions of culture as well as the layered dimensions of diversity.

Though traveling can yield various interactions, most people do not have the capacity nor the opportunity to travel. Though being surrounded by those of various ethnicities can expand our cultural viewpoints, most people do not grow up in a multi-diverse household nor learn three languages by the age of five. While these circumstances may increase the likelihood of feeling culture shock in the future, they are normal and perhaps even inevitable. The weight should not be placed on the shoulders of individuals to expose themselves to different cultures; it should instead be placed on communities to provide localized opportunities to experience diversity.

The weight should not be placed on the shoulders of individuals to expose themselves to different cultures; it should instead be placed on communities to provide localized opportunities to experience diversity.

This is, however, not the case. Many communities have difficulty providing diverse opportunities, and there is a main reason why.

During her sophomore year at LaRue County High School, Jada Hunter-Hays, an African-American, had the choice of applying to two highly selective public boarding schools: the Craft Academy located in Eastern Kentucky on the campus of Morehead State University or the Gatton Academy located in Western Kentucky on the campus of Western Kentucky University. Now, almost halfway through her junior year at Gatton, she reflects upon making the right decision.

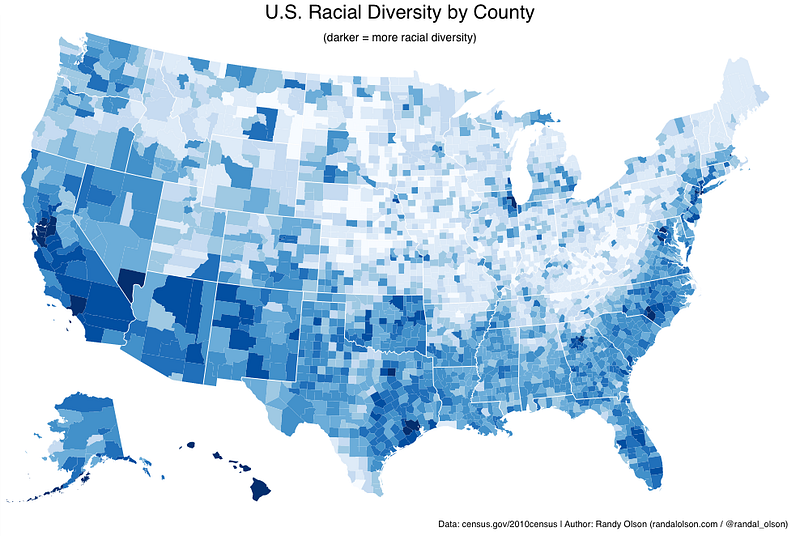

Before attending Gatton, Jada lived in Hodgenville, KY, which is approximately two and a half hours from Craft. In spite of the distance, she did not have to live near the area or even have been to the area to have heard the rumours. Eastern Kentucky is a region of the state with minimal diversity. Hearing from word of mouth of those in the area and conducting a simple search into the racial demographics, it was easy to prove this to be true. She remarks, referring to Gatton, “Even before I came here, I felt that WKU offered more diversity than Morehead. I just didn’t get that feeling from Eastern Kentucky.” Since a young age, Jada has had exposure to various cultures and has experienced learning from different cultural perspectives. She says, “When you have experienced seeing from different cultural perspectives, it can be difficult to go to a place where you cannot do that.”

Jada’s story is only one of the forms of culture shock. Even if you prepare yourself and are aware of what to expect, the effect of culture shock is a multifaceted feeling that encompasses more than a notion of alienism. Moreover, when it is experienced firsthand, the feeling can be markedly augmented.

Another Gatton Academy junior and Haitain-American, Christine Belance, shares her sentiments during the Craft/Gatton selection process. Christine previously attended Fairdale High School in Louisville, KY, a school with a low proportion of minorities. When mentioning the possibility of going to Craft to her teacher, she says, “I was warned by my teacher who actually went to Morehead that the area wouldn’t be diverse, so I expected it.” Christine was familiar with being in an environment with few minorities, therefore going to Eastern Kentucky to see the culture directly did not invoke any preconceived feelings of culture shock.

“I just didn’t expect HOW non-diverse the area actually is.”

Once she arrived in Eastern Kentucky, it became possible for her to grasp the extent of the diversity in the area and to draw upon her own conclusions rather than those of others: “I just didn’t expect HOW non-diverse the area actually is,” she says. The total number of African-Americans was blatantly discernible — less than a handful. She did not want to end up simply being a number, simply one of the *insert minority*. She adds, “I don’t want to be accepted just because I’m black. And it’s the same for those who are Vietnamese, Chinese, etc. You don’t want to just be accepted because of your color.” When you are only a minor portion of the entire population, it becomes easy to stand out racially.

A community’s reputation for having little diversity hinders its ability to attract those of different cultures and to actually provide diverse opportunities for the people there. We then ask, what can a community do to change that reputation? How does it escape the endless cycle of being stereotyped “white”, pushing people of color away, and then being dubbed, once again, as being white?

Hunter Hayden, an African-American junior at Craft Academy and previous student of Henderson County High School, presents an alternative perspective. Hunter, like Jada and Christine, had the choice between Craft and Gatton. Like Jada and Christine, Hunter also had exposure to various ethnicities growing up. However, instead of that factor causing her to to pursue areas with more diversity, she has instead been conditioned to accept all cultures and to seek to be open-minded.

Owing both to her religious beliefs and morals taught to her by her parents, she explains, “My parents raised me to not judge someone by the color of their skin and to love everyone.” Whether or not you have the same skin color as someone else, you can connect with them on various other aspects such as common interests or similar personalities. She adds in regard to facing racial conflicts, “You will always find someone with something negative to say, but you never know the reasoning behind it. You don’t know how they grew up or what they were taught. Instead of taking their comments to heart, try to have an open mind.”

Hunter’s experience begs the factor of values we believe in. The location where we grew up may be the same or it may be different; it is instead our perception of our community along with the way we were taught to see right and wrong that holds the greatest significance.

How does [a community] escape the endless cycle of being stereotyped “white”, pushing people of color away, and then being dubbed, once again, as being white?

Looking beyond the black and white divide, culture shock entails other ethnicities as well. The presence of African-Americans may be minimal in Eastern Kentucky, but the presence of Indians is even fewer to almost none in some areas.

One of the two current Indians at Craft, junior Kavya Vasudevan provides a rare perspective. Born and raised in Frankfort, KY, Kavya attended Western Hills High School where she grew up around a variety of cultures. When she made the choice between Craft and Gatton, rather than pursue the latter where she could continue to be surrounded by those who are the same ethnicity as her, she expresses, “I would be a minority at Craft. I don’t want to be just another Indian among fifteen other Indians or one Asian among thirty other Asians.” As one of the minute numbers representing her race at Craft, she automatically stands out.

To Kavya, ethnicity is not the catch-all characteristic she defines people by: “Even if I went somewhere where people had the same ethnicity as me, I would still be excluded because I don’t know them. They’re strangers. Having the same ethnicity does not automatically connect me to someone. I would still have to go through the same process as with someone of a different ethnicity to get to know them.”

Race can contribute enormously to an individual’s identity, and it is easy to see someone for their superficial appearance. Yet, it is important to remember that, like a variety of other classifications (name, gender, sexual orientation, appearance, etc.), it is not something someone chooses to be born as, and it does not wholly reflect who they are.

Kavya further notes that fewer people at her high school have heard of Craft. Now, because she chose to come here, other students will be more likely to do the same.

“Having the same ethnicity does not automatically connect me to someone.”

This is the concept of diversity beckoning more diversity, or simply, a pioneer setting an example for others to follow.

Although communities with little diversity may be at a disadvantage, the little diversity they do have can prove to be advantageous. By demonstrating to outsiders that they can provide a welcoming and accepting space for people of color, communities can then increase their prospects of attracting them there. But it’s not just a matter of not being racist. Taking no action is just about the same as taking negative action.

One simple method to promote culture and cultural awareness is by holding diversity festivals. Though these festivals may only be able to reflect a small portion of the multitude of diversity around the world, it gives an opportunity to people in the region to be introduced to different cultures. A prior experience and knowledge that a culture exists builds the foundation for further research into that culture.

Another method any individual can do that requires minimal effort is to communicate with the few diverse people in your community. If you have ever wondered why the practices of a person of color seem unusual, ask them directly. If you want to learn more about a person of color’s background, ask them directly. Rather than make assumptions or let ignorance override your curiosity, initiate a conversation with them. Curiosity is not offensive. Though it may be a learning experience for all of those interacting with the person of color, it is just as much a learning experience for the person of color as they endeavor to assimilate the community’s customs. Always strive to openly communicate as it is the basis to understanding the cultural nuances unfamiliar to you.

Ultimately, even if a community is unable to attract diverse individuals or does not have a presently diverse population, there are other approaches that can be taken to bridge the cultural gap. Teachers can set up a pen pal system for students to write to other students across the world. Schools could promote learning foreign languages or establish a culture club within their institution. Using technology, students could video call other students in different countries and ask questions.

The migration towards cultural change is a lengthy and arduous process. Still, all change starts small. And like all change, it is a process to be contended both outside of an individual in their community and inside of an individual within their own lifestyle. By simply seeking to educate ourselves and the ones around us, showing that we are willing to listen to different cultural perspectives, and welcoming people of color with open arms, we can reduce the effects of culture shock and move towards a diverse future for everyone.

Amy Yang is a junior at Craft Academy.

The opinions expressed on the Forum represent the individual students to whom they are attributed. They do not reflect the official position or opinion of the Prichard Committee for Academic Excellence or the Student Voice Team. Read about our policies.