Summer slide — (n.) summertime loss of achievement gains

A google search of “summer slide” garners thousands of results, a large portion of them self-help articles explaining how to keep your child’s brain sharp during the summer. My mother surely did her research. I can recall — with great clarity — trudging through my summer math workbook, glancing longingly at the sunlight filtering in through my bedroom windows.

But the great irony is that children whose parents a) know what “summer slide” is and b) are so concerned with the prospect of summer slide that they are driven to conduct a google search, are not those most at risk. The children most at risk are those whose parents do not have regular access to a computer, who are not engaged in their child’s education, and who are certainly not aware of trendy education policy buzzwords.

These children come from low-income backgrounds. They can’t afford the “summer fun” on which American parents spend $16.6 billion each year. While their better-off peers attend summer camp, play outside, read books (likely at the prompting of their guardians), and travel, these children prematurely assume the role of caregiver, watching their younger siblings while their parent(s) works long hours. Their parents are not able to buy them books or take them on adventures. Their neighborhoods are not safe for playing. They have no money to pay for summer camp. And while their peers expand — or, at the very least, maintain — their knowledge base over the course of the summer, these children, lacking opportunities for stimulation, lose much of what they gained during the school year.

This is “summer slide.”

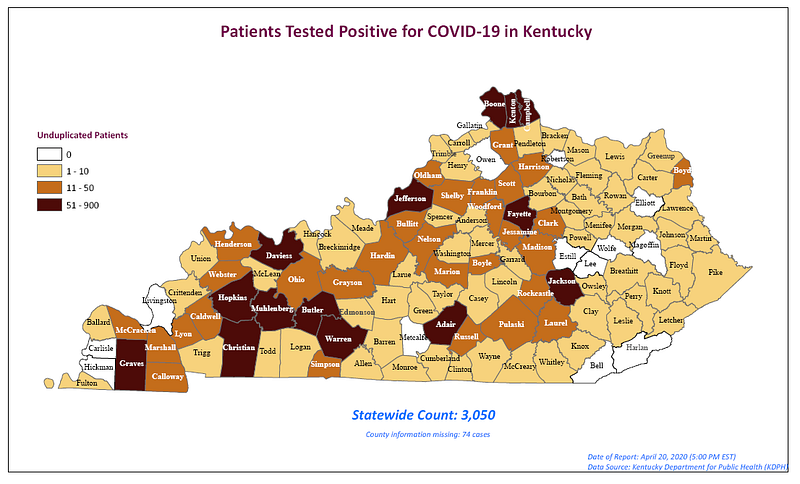

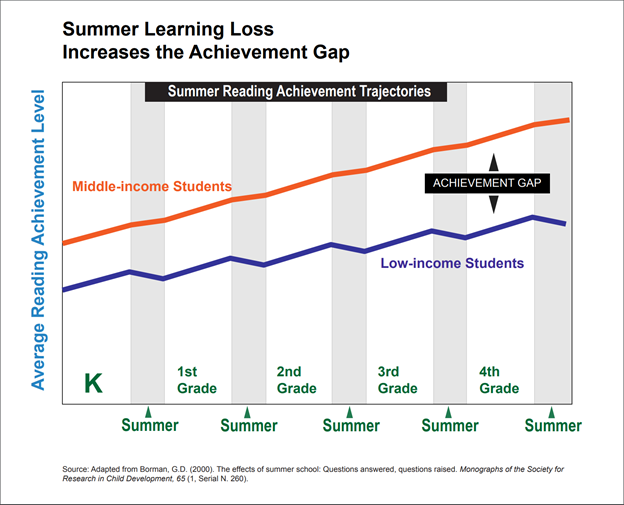

The witty, alliterative name, which sounds vaguely like a line dance or a cocktail, belies the destructive nature of this phenomenon. Education policy experts think that summer slide is a significant driver of the achievement gap between low-income students and their more well-off peers. Consider the following:

- Fewer than 4% of kids from the lowest income bracket participate in summer camps, compared to 18% of kids from the highest income bracket.

- Children in low-income houses fall behind in reading and math by about two months during the summer.

- 90% of teachers say they must spend three or more weeks re-teaching material at the beginning of the school year.

Even more alarming is the fact that affected students don’t catch back up to their peers when they return to school in the fall; summertime learning losses are cumulative. A John Hopkins study followed a cohort of low-income and mid-income students from first grade to college and found that by fifth grade, low-income students were on average three years behind their peers even though they made comparable gains during the school year. Students who cannot read proficiently by the third grade are four times more likely to drop out of high school. The ability to read is a crucial prerequisite to success in the classroom, particularly given the American education system’s reliance on standardized testing as a tool for accountability.

So, while inequities in summertime activities may not initially appear to be a cause for concern, the resulting slide in gains presents a clear threat to schools’ mission of providing a high quality education to all students. Those 70 days that students lose touch with learning serve to sort the privileged from the underprivileged, pulling low-income, minority, and otherwise underrepresented students deeper into the quicksand of poverty.

During the school year, we provide students with a plethora of lifelines: free meals, after-school programs, tutoring services. But those services largely drop off once school lets out. For example, six out of every seven students who rely on free-and-reduced lunches during the school year lose that aid during the summer.

This intermittent support system is hardly supportive — would you build a house on a foundation ridden with holes? Affordable summer camps promoting fitness, creativity, group work, hands-on learning, and the arts could play a large role in filling those gaps. Students — regardless of who their parents are or where they grew up — deserve year-round opportunities to stretch their minds.

I have watched fellow students struggle to keep their heads above water. I have spoken with students who started the school year fifty meters behind their classmates and came to accept that they would never be able to catch up. It is all too easy for them to drown.

In fact, it’s as easy as going down a slide.

Eliza Jane Schaeffer is from Lexington and is a rising sophomore at Dartmouth College.

The opinions expressed on the Forum represent the individual students to whom they are attributed. They do not reflect the official position or opinion of the Prichard Committee for Academic Excellence or the Student Voice Team. Read about our policies.